As a damp specialist I get asked about damp all the time. So this post is the start of a short series of plain English articles for ‘normal’ people – not surveyors or other property professionals.

To keep things simple, we need to think first about how to limit ourselves to damp which we all can relate to:

Water running down windows and walls

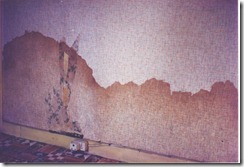

Mouldy clothing & peeling wallpaper

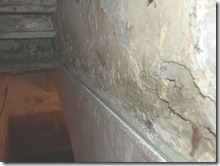

Staining on walls, with bubbling paint & paper

Algae stains down walls (outside)

White furry deposits on plaster inside or on bricks/stones outside

Crumbling plaster

In these articles I am not going to talk about damp which is invisible, which is discovered using a ‘damp meter’. Surveyors and specialists use terms like rising damp, penetrating damp & condensation. These are useful labels, however, they describe the pathway of the moister, rather than the cause. Rising damp can mean many things, it just refers to moisture with a source at the base of a wall. Penetrating damp refers to water doing just that; ‘penetrating’ through a wall. It can be a leaky gutter, poor pointing between the stones or bricks or high path levels, amongst other things. Condensation is dew forming on surfaces and is caused by many practical things. So let’s get right back to the basics and lable damp by what it looks like, smells and feels like. Let’s also use what we see, hear and smell to rule out some common causes.

Here are some simple ground rules you can use to help find out why your house is damp.

If a wall feels wet to the touch, with your hand coming away wet when when you touch it – it is not rising damp

It is also unlikely to be penetrating damp (unless you have a truly torrential water leak, which should be obvious).

If the damp is on walls upstairs – it is not rising damp

If the damp is mouldy and smelly – it is not rising damp.

If the damp causes mould on clothing or shoes in cupboards – it is not rising damp

Condensation.

So what is it? Well, we’ve ruled out Rising damp and there’s no torrential water leak, so that leaves one very common cause. That is water condensing out of the air and physically wetting the walls. It doesn’t have to be so bad that clothes are wet for mould to grow on them, if air is just below the point where dew would form, mould will grow.

Sometimes a wall may be stained with mould, yet feel dry to the touch. Usually this is because dew is forming for relatively short periods and is then evaporating so that when you touch the wall, it is dry. Try checking the wall at other times, say during the night or very early morning and you’ll often find that your hand comes away wet with dew. Mould can survive with a short ‘watering’ once every day or so, the spores survive the dry periods and get growing again when the environment is right.

Almost all houses will suffer occasional condensation; we’ve all seen the mirror steam up when we take a bath or shower. This soon evaporates and isn’t an issue. For similar ‘steam’ to form on walls and ceilings, other than in a bathroom or kitchen, a couple of factors are involved.

- The air has to be quite humid

- There needs to be a cool surface which can cool air in contact with it and cause condensation.

The two are interchangeable, so that you could have slightly damp air, which would not normally produce dew, forming dew on a surface because the surface is much cooler than the air. This is the common cause of steamed up single glazed windows and the dew we see running down a cool glass of beer.

On the other hand, there can be very moist air, which is near saturation and in effect desperate to cause dew, yet the room and surfaces are so well heated (or insulated), that there is no surface cool enough to cause dew to form, so the room is just warm and maybe a bit ‘stuffy’ but apparently dry.

This means that dew formation is avoided by a combination of two factors; keeping the amount of water in the air as low as practical and maintaining reasonable heating and insulation.

Just to put things in perspective, let’s think about why it is that air in our houses can become moist enough to form dew (condensation), on wallpaper or paint.

Modern housing and older housing, which has been modernised, is not well ventilated. Older houses relied on open fires for all heating and cooking. Open fires consume large amounts of oxygen as they burn, air is constantly drawn up the chimney and is replaced by air sucked in through draughty windows and doors. The air drawn into the fire contains the humidity we create, breathing, cooking, washing and drying clothes – the air from outside the house is much dryer (yes – even in winter), so older houses had a balance, whereby excessive humidity didn’t build up much. In addition, our grandparents thought that a bath once a month was about right, for a sensible person. So there wasn’t that much humidity created from the bathroom; even with a larger family.

Contrast this with how we live today. Most people shower or bath every day. Most fireplaces have been bricked up, or a have a gas or electric fire in the hearth which is rarely used. The draughty windows and doors have gone for good.

It gets better; if there are girls in the house, expect two showers or a shower and hair wash daily; there’s a dishwasher and power shower, a microwave, washing machine and we have a mountain of clothes which are only ever worn once, before they are washed and dried; sometimes on clothes drying racks, which modern heating will ‘air dry’ in the hall, lounge or bedroom. We have electric kettles which produce tea and steam, at the flick of a switch.

All this means that we have a double bubble when it comes to condensation – our houses are much wetter and the ventilation is much worse too.

Anyway, how can we stop the condensation from becoming such a problem; that we have mould and peeling wallpaper?

Recognising the above causes and accepting these facts is the first step to getting control. the double glazing is staying, as are all the modern appliances and we aren’t going back to bathing only when there’s an ‘R’ in the month.

So what to do? Well, first thing. Is there a working extractor fan in the bathroom? Is it used every time the bathroom is used? Ideally, a unit which activates every time the bathroom light is switched on is needed. Better still, a fan which continues to run for five minutes after each operation – even when the light is switched off.

If there is a fan, is it ducted out of the building properly? If it’s in the ceiling or not on an outside wall, there must be ducting leading to an external vent – check it. The fan is useless without it. When the fan is operating, can you put a sheet of A4 paper over the grill and leave it hanging by the suction? If not, then the fan is either defective or is not powerful enough (this can be caused by too many bends in ducting too).

Next – repeat for the kitchen. A cooker hood may look nice and have the latest in ‘carbon filtration’ but this will not remove moisture from air. Check that any cooker hood has a ducting kit, leading to an outside grill. Without a duct it is useless. It must be used when cooking, boiling a kettle or washing pots. If there’s no hood, then install an extractor fan – minimum 150mm diameter and it must be diligently used.

Extractors work just like an open fire would. They expel air, with the moisture and such in it. This is replaced by dryer air, which is drawn in via small gaps and ventilation grills, such as the very small ones over windows. If you can find these ‘trickle vents’, then do check they are open and leave them open.

Taking into account the differences in lifestyle and housing which has happened over the last 50 years or so – the extractors in bathrooms and kitchens are the most undervalued essential components of a modern house. If they wear out, break or are neglected, condensation problems will almost always follow.

The next thing is keeping an eye on moisture production. Okay, we still have to dry clothes, but remember how heavy those clothes were, fresh from the washing machine? And how light they are when they’ve spent a few hours on the clothes rack or radiator? All that weight loss is water, which is now in the air. So it is sensible to try to limit that. This can be done by using one room as the drying room, rather than having wet clothes willy-nilly, all over the house. The drying room can be gently heated and the window opened to let the warm moist air get out – remember to keep the internal door to that room closed, so that the warm moist air doesn’t spread around the house and cause more condensation. If you can, try to avoid drying clothes this way (apart from a tea towel and bath towel in the kitchen and bathroom of course).

If the above is in place and there are still issues, then that’s the time to ask for specialist advice. There may be walls which are colder than they should be – causing condensation even in relatively ‘dry’ environments, or other causes, which need a bit more investigation.

Dry Rot.

PS – want to know about other causes of damp? Try The very basic guide to damp Part 2 and Part 3

Bryan,

If OK with you I will ADD this page/link from my Damp “services” pages as a further reading place for people hitting our site ? Am still trying sort out getting to the PCA AGM – would be great to meet you at last ! Annabelle

Hi Annabelle,

I’m glad you like it and think it would be useful for your readers. A link would be great – cheers. I think that we small independents can help each other get the message across to consumers that there are good specialists out there, who care enough to be trusted to give good advice and I know I can include you in that group.

I can’t make this years AGM unfortunatly because I need a rest from work and the time off is now re-booked for a weekend in London, with a show, some nice food and some shopping (plus a museum or two), can’t wait.

We’ll meet up soon – maybe an independent specialist day at the PCA or something? I could have a chat with Graham and Steve and maybe we could get a day of bespoke training set up?

All the best and keep up the good work.

Bryan

Thank you so much for that really useful article on damp caused by condensation. Makes so much sense of what is happening in our old house.

Hello I am not sure if you can give me some advice please.

I am in a rented terraced property. I have really bad mould on inside walls as well as external walls on the window frames and window ledges. On the ceilings to. The mould has gone white and green furry in some places. I have extremely bad mould in the bathroom so bad I have flies/bugs crawling all over the ceilings and on the bath tiles. I open windows every morning and close them and put heating on every afternoon/eve. Can someone give me some advice on clearing it. I’m concerned for our health also?! Thank you

Hi Helen,

You must speak to your landlord about this. here’s a post on similar issues which may help you http://www.preservationexpert.co.uk/my-council-house-is-damp/

Bryan